The highly educated often have two children — childlessness and high numbers of children more commonly seen among low- and medium-educated persons

FLUX Policy brief — Knowledge to support better decision making

1/2022

Marika Jalovaara, University of Turku and INVEST Flagship

Anneli Miettinen, Kela and INVEST Flagship

Main findings

- Lifetime childlessness has increased among men and women with lower (low or medium) education. Childlessness levels in Finland are high by international standards.

- Simultaneously, high numbers of children are commonly seen among lower-educated men and women. Often, couples with lower level of education have three, four or more children. This is linked to an increase in ‘multipartner fertility’, or, having a child with more than one partner.

- Highly educated men and women are more likely to have exactly two children. Both childlessness and a high number of children are less common among highly educated persons than among the lower educated, and this has not changed.

At the core of demographic research is the study of the link between education and fertility – a topic of great societal importance (Lutz et al. 2017). It informs on how education and the economy shape populations. Educational differences in fertility matter greatly for population dynamics. They inform on potentially gendered social inequalities in opportunities for family formation.

Mainly, a family increases an individual’s resources and well-being and protects them from risks. However, partnership instability and childlessness have steadily increased. In contemporary Finland, the lack of family ties is most common among men and women who already are in a more vulnerable position by low, e.g., education and income. As such, socioeconomic differences in family dynamics are prone to exacerbate the accumulation of inequalities both during an individual’s life course and intergenerationally.

The aims of our study

Fertility levels can differ significantly between educational groups. These differences are not straightforward. They may vary between countries, differ between men and women, and may change along with shifting societal circumstances (Wood et al. 2014; Sobotka et al. 2017). Our new study shows that fertility patterns also vary within educational groups. Childlessness and the number of children tell separate stories of fertility differences between and within educational groups.

Our prior study into the Nordic countries (Jalovaara et al. 2019) showed stable and strong differences in fertility levels across educational groups among men. For example, levels of lifetime childlessness are higher among lower educated men.

For women, on the other hand, the differences between educational groups have changed entirely. For example, lifetime childlessness used to be most common for highly educated women, whereas currently their childlessness level stands the lowest. In other words, the association between education and childlessness had become similar to what it has been for males longstandingly. This shift is characteristic to the Nordic countries, and reflects increasing gender equality in these societies.

Our new study (Jalovaara et al. 2021) focusing on Finland and Sweden adds to prior research in the following ways:

- Fertility measures based on overall averages can mask significant differences within groups, and important patterns may remain unobserved. For instance, if a group were characterised by both childlessness and high child numbers (3+), an average (of, say, 2) describes the group’s fertility behaviour poorly. We inspected fertility trends by the order of birth and investigated realised childbearing also with data on number of children ultimately born.

- The effect of changing partnership dynamics on fertility patterns has gone relatively unnoticed. Our study examined how having children with more than one partner contributes to differences between educational groups.

- Most research on fertility continues to be centred on women, and evidence pertaining to men is sparse. Gender comparisons complement the picture and add to the understanding of shifts in gender roles both in public and private spheres.

Our study focused on fertility developments and educational differences in having children in Finland and Sweden, among men and women born between 1940 and 1973/78. We used individual-level register data encompassing the entire populations in both countries.

We studied actualised fertility among women and men, at age 40 and 45, respectively. A small number of men and women have children above these ages, but the figures are near final.

Studying actualised fertility pertains to those who have passed their childbearing years. This allows the study of actual life histories of generations and within subsets of the population. Studying educational fertility differences in effect requires this approach. It does not directly show which (younger) population groups contribute the most to the recent fertility development (see Hellstrand et al. 2020), but studying the differences in population subgroups highlights factors that may explain the shifts observed today.

The results are presented by educational level. We used information on a person’s highest attained degree to form three groups: low (compulsory basic level), medium ( upper secondary level) and high (tertiary level) education. During the observation period, marked changes occurred in the educational attainment of the population: the share of low-educated has dropped from 48 percent to 14 percent for men and 48 percent to 5 percent for women. Of persons born in the 1970s, already half have acquired tertiary degrees – 40 percent for men and 60 percent for women.

With the educational level rising, the people having no education beyond the basic level are an increasingly small group and marginal in terms of their labour market status, for instance. However, what was a family dynamic typical for the low-educated has become more common in the medium-educated population – of the men born in the 1970s nearly half, and a generous third of the women, hold medium (i.e., upper secondary) education as their highest qualification.

This policy brief reports some of the key findings in our research article (Jalovaara et al. 2021).

Lifetime childlessness most common among the lower educated

An increasing proportion of low- and medium-educated men and women remain childless.

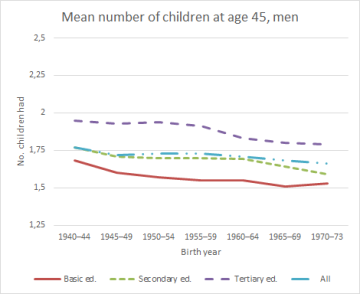

For men the differences between educational groups are remarkable (Figure 1). Of low-educated men born in the beginning of the 1970s, over a third (35%) were childless at the age of 45. For their medium-educated peers this figure also approached one third (31%). In contrast, the childlessness level for highly educated men stood at one fifth and has not increased in recent times.

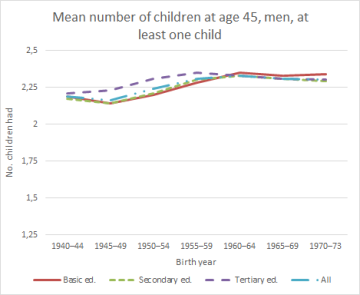

Figure 1. Mean number of children, share of childless and mean number of children for those with at least one child. Men at age 45, Finland

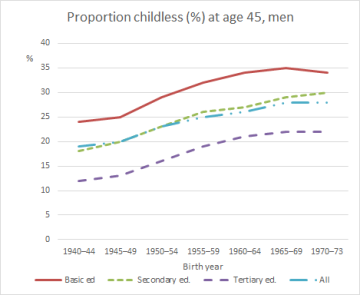

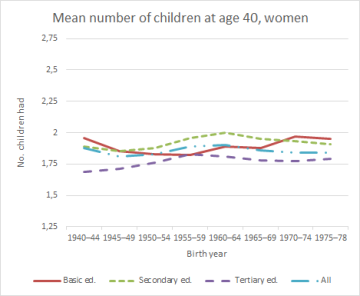

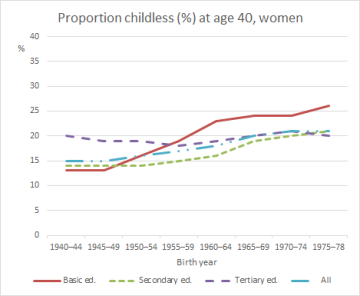

For women, lifetime childlessness is currently the highest for those with low education (Figure 2). The association between education and childlessness for women has changed drastically: among women born in the 1940s and 1950s, those with high education were most likely to remain childless. Since then, childlessness has become more common for lower (low or medium) educated women, but not for the highly educated.

Figure 2. Mean number of children, share of childless and mean number of children for those with at least one child. Women at age 40, Finland

Of note, in Finland, levels of lifetime childlessness have also increased among medium-educated men and women. In contrast to Sweden, this increase is not confined to the small group of low-educated persons.

High numbers of children have also become common for the low- and medium-educated

Meanwhile, having a large number of children has become more common among low- and medium-educated persons.

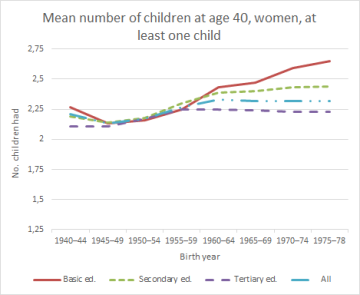

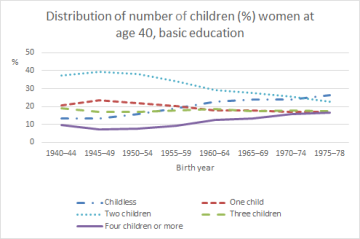

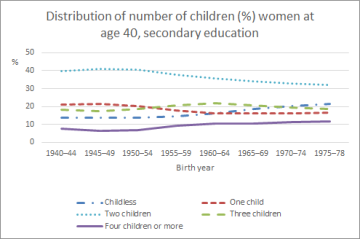

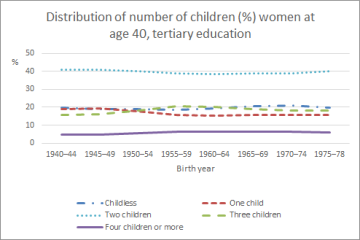

Among low- and medium-educated mothers (women with at least one child) the average number of children has clearly increased (Figure 2). This is driven by the increasing share of mothers in these groups who have had three, four, or more children. (Figure 3). Two as the final number of children is ever rarer for low- and medium-educated women.

Figure 3. Distribution (%) of number of children by education group. Women at age 40, Finland

A similar change can be seen among low- and medium-educated men. Though these lower educated men more often remain childless than their highly educated peers, the average number of children for fathers (men with at least one child) do not differ, as lower educated fathers tend to reach higher number of children.

Link between changes in partnership dynamics and greater number of children

An ever increasing share of low- and medium-educated mothers and fathers having children with more than one partner is largely behind the greater numbers of children of these lower educated groups.

Among low-educated mothers born in 1975–1978, nearly a third of the second children are with a different partner than the firstborn. In the case of the third child, the figure is exactly half, and 59% for the fourth and subsequent children. Among their medium-educated peers, the respective numbers are also relatively high: of the second children 14%, 30% of the third and 39% of fourth and subsequent children are with a new partner.

The development has been linked to an increase in partnership instability. Increasing proportions of mothers and fathers separate or divorce and have a child with a new partner. Rates of separation and divorce are higher among the lower educated (e.g., Jalovaara & Kulu 2018). In addition, lower educated mothers are more likely than highly educated mothers to have a child when they are not cohabiting or married (Jalovaara & Andersson 2018; Jalovaara 2020).

Highly educated men and women often have exactly two children

Compared to other groups, highly educated men and women more commonly have exactly two children. Unlike their lower educated peers, having two children has not grown less common.

Lifetime childlessness has not become more common for higher educated men and women recently. A more detailed analysis even showed a decrease in lifetime childlessness among women with higher tertiary degrees, in other words, opposite trends for low and high educated groups.

Summary

In addition to the differences in fertility rates between the low- and high-educated, the lower educated groups show changes over time in two directions. This is part of a change we refer to as dual polarisation. On one hand, the family formation among low- and medium-educated persons is often characterised by non-occurence, as in never partnering and lifetime childlessness. On the other hand however, if a family were started, changes such as union dissolution and having children with more than one partner, occur more frequently and at an earlier age.

Instead, family formation among highly educated men and women seemingly adhere to normative ideals. Many will eventually separate or divorce from their childbearing partner but children tend to be born with the same partner.

In prior decades, the level of education has had differing effects on men and women’s fertility, but this difference has narrowed in both Finland and the other Nordic countries. High education and the financial stability brought thereby likely facilitates family formation among both men and women.

Lifetime childlessness is often linked to never partnering or partnership instability

A common view to this day is lifetime childlessness being most common among tertiary-educated women hesitating to form a family due to their careers. Though this holds true elsewhere in Europe, the association has changed in the Nordic countries: it seems that the tertiary-educated are better able to realise their desires regarding family formation than lower educated men and women. Lifetime childlessness is most common for the lower educated, that is, those whose position in the labour market is the weakest.

One central factor connecting low education and childlessness is the absence of a long partnership. Our prior study (Jalovaara & Fasang 2017) showed majority of childless individuals either have had shorter cohabitation periods, or never to have cohabited or been married at all. Such partnership histories are specifically een in low-educated populations. At the same time, the change in partnership behaviour, and especially growing separation numbers, can be seen in the larger than average number of children being had.

Differing opportunities to realise familial aspirations

Though surveys show that voluntary childlessness has become more common (Miettinen 2015), the majority of men and women wish to have a stable partnership and become parents at some point. These desires and aspirations are most commonly realised by those with the best educational and financial opportunities for their fulfilment. Educational differences in childlessness suggest that there are differences in not only desires and aspirations, but also in the opportunities for their fulfilment.

Our studies show that stable employment specifically encourages family formation at all stages: partnership formation, marrying, partnership stability and having children (e.g. Miettinen & Jalovaara 2020). For example, long-term unemployed men rarely move in together with a partner or marry – in addition, if they are partnered they are more likely to separate or divorce. Consequently, they are less likely to become fathers. The associations between employment and family transitions are similar among women in Finland. Highly educated men and women benefit from both more stable employment, and more stable partnerships, both of which facilitate parenthood. Therefore, policies in support of high employment rates are important from the vantage point of fertility rates as well.

Successful education policies support family formation

Successful education policies are essential to ensuring wellbeing. Education is associated with practically all facets of wellbeing. In Finland, its relationship with family formation and partnership stability is positive for men and women alike. The expansion of mandatory schooling and costless secondary education likely decreases the proportion of those with only basic education. However, also medium-educated men and women increasingly face obstacles to family formation and stability. This development and its causes warrant further recognition.

At the same time, attention should be paid to the transition from education to working life and the opportunities to support family formation during studies. The postponement of having children beyond age 30 is already very common among the highly educated, and though many reach their desired number of children despite late entry into parenthood, the rise of the average age of having children also leads to an increased risk of involuntary childlessness.

In supporting family formation, the target population of special interest ought to be those who do not yet have a family. Traditional family policies (such as child benefit, family leaves, daycare) are necessary and play an especially important part in the well-being of children and their parents, but not enough if the aim is to increase fertility. In contemporary Nordic societies, the barriers to family formation more often come from lacking, fragmented or unstable partnerships or employment careers, rather than from high career aspirations and tight work schedules. This requires a more encompassing view on social and family policies. A broad approach to the well-being of children and adults supports family formation and the stability of families while tackling financial and social inequalities.

Authors

Marika Jalovaara is associate professor (docent), the director of FLUX consortium and research theme director in INVEST research flagship at the University Turku. Her research mainly focuses on fertility and family dynamics and their linkages with social inequalities.

Anneli Miettinen works as a senior researcher at Social Insurance Institution (Kela). Her research has focused on fertility and gender equality in reconciliation of work and family, and in childcare.

email: marika.jalovaara[at]utu.fi and anneli.miettinen[at]kela.fi

References

Hellstrand, Julia, Jessica Nisén, Mikko Myrskylä (2022). Less partnering, less children, or both? Analysis of the drivers of first birth decline in Finland since 2010. European Journal of Population.

Jalovaara, Marika (2020). Erkanevia elämänkulkuja? Sosiaalisen aseman yhteys lasten perhemuotoihin [Diverging destinies? Socioeconomic differences in children’s family forms]. Kallio, Johanna & Mia Hakovirta (eds.): Lapsiperheiden köyhyys & huono-osaisuus, Vastapaino.

Jalovaara, Marika & Anette Eva Fasang (2017). From never-partnered to serial cohabitors: Union trajectories to childlessness. Demographic Research 36(55): 1703–1720.

Jalovaara, Marika, Linus Andersson, Anneli Miettinen (2021). Parity disparity: Educational differences in Nordic fertility across parities and number of reproductive partners. Population Studies 76(1):119–136.

Jalovaara Marika, Gunnar Andersson (2018). Disparities in children’s family experiences by mother’s socioeconomic status: The case of Finland. Population Research and Policy Review 37(5): 751–768.

Jalovaara, Marika, Gerda Neyer, Gunnar Andersson, Johan Dahlberg, Lars Dommermuth, Peter Fallesen, Trude Lappegård (2019). Education, gender, and cohort fertility in the Nordic countries. European Journal of Population 35(3): 563–586.

Lutz, Wolfgang, P Butz William, & KC Samir (Toim.) (2017). World population & human capital in the twenty-first century: An overview. Oxford University Press.

Jalovaara, Marika, Hill Kulu (2018). Union duration and union dissolution: An immediate itch? European Sociological Review 34(5): 486–500.

Miettinen, Anneli (2015). Miksi syntyvyys laskee? Suomalaisten lastensaantiin liittyviä toiveita ja odotuksia. Katsauksia E49/2015. Helsinki: Väestöliitto.

Miettinen, Anneli, Marika Jalovaara (2019). Unemployment delays parenthood but not for all. Life stage and educational differences in the effects of employment uncertainty on first births. Advances in Life Course Research 43: 100320.

Sobotka, Tomáš, Éva Beaujouan, & Jan Van Bavel (2017). Introduction: Education and fertility in low-fertility settings. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research 1: 1–16.

Wood, Jonas, Karel Neels, & Tine Kil (2014). The educational gradient of childlessness and cohort parity progression in 14 low fertility countries. Demographic Research 31(46): 1365–1416.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Robert Stowe for his help with drawing the graphs and translating the text in English.

The research has been funded by the Academy of Finland (decision numbers 321264 for the NEFER project and 320162 for the INVEST flagship) and Strategic Research Council (decision number 345130 for the FLUX consortium).