More children under 3 attend early childhood education and care – progress slower in Finland than elsewhere in Europe

Policy brief

03/2024

Sanni Välimäki, Johanna Lammi-Taskula, Merita Mesiäislehto & Johanna Närvi

Main findings of the study

- The European Union’s target is that 45% of children under three should participate in early childhood education and care (ECEC).

- The participation of children under three in ECEC has increased in most European countries during the 2000s. This has also happened in Finland, but at a slower rate than in other countries.

- Children of highly educated mothers are more likely to participate in ECEC, and in recent years the disparities between educational groups have increased in many countries.

- In Finland, children of low-educated mothers remain outside early childhood education for longer than others. This is mainly due to the long-term use of home care allowance.

Early childhood education and care services (ECEC) make it easier for mothers and fathers to combine work and family life. Furthermore, ECEC has been found to have positive effects on children’s development, especially for children with fewer socio-economic resources (Van Huizen & Plantenga, 2018). At the same time, however, it is known that in European countries, children of highly educated parents are more likely to participate in ECEC (Pavolini & Van Lancker, 2018). The European Union’s target is that, by 2030, almost all children aged three and over will be enrolled in early childhood education and care. For children under three, the target is 45%.

The aim of our recent study was to get a picture of how the association between participation in early childhood education and parents’ socio-economic status has changed in Europe between 2004 and 2019 (Välimäki et al. 2024). In this study, we are particularly interested in the association between maternal education and childcare choices for children under three years of age.

In Finland, the home care allowance is a popular benefit, but participation in early childhood education and care has become more common

In Finland, children have a subjective right to early childhood education regardless of their parents’ work situation. The right starts at the end of parental leave. Such a right is rare in Europe. Moreover, the fees are income-related and are not paid at all by low-income parents. In this respect, Finnish family policy strongly supports the participation of all children in early childhood education and care.

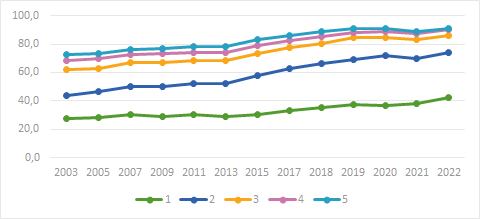

However, participation rates are low, especially for children under three (Figure 1). This can be explained by the home care allowance, which allows parents to look after their children at home after parental leave as an alternative to early childhood education. Home care allowance is a popular benefit that is used by the majority of families for at least some time after parental leave (Miettinen & Saarikallio-Torp, 2023). Longer periods of absence from paid employment are made possible by child care leave, which an employee is entitled to if they care for a child under 3 years of age at home.

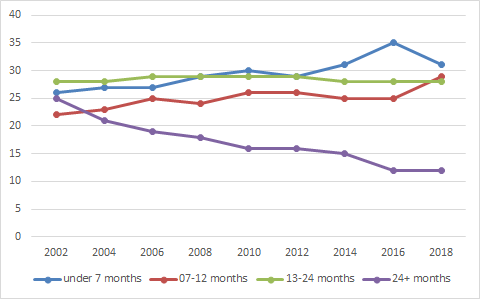

However, participation in early childhood education and care has increased in the 2010s, especially for two-year-olds, while the share of the longest periods of home care allowance has decreased (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Proportion of children in early childhood education and care by age group (1-5 years), 2003-2022, % (source: THL – Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare & Statistics Finland).

Figure 2: Share of home care allowance (HCA) periods of different lengths among HCA users after parental allowance periods that ended in 2002-2018, % (source: Kela – The Social Insurance Institution of Finland).

Participation rates have increased in all European countries

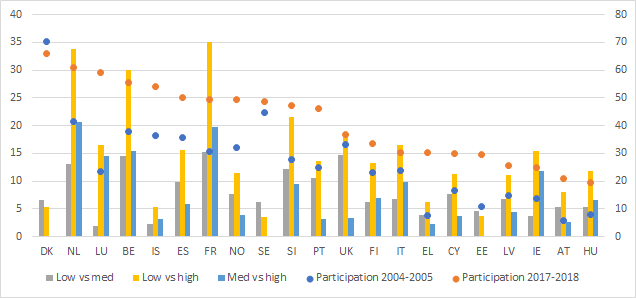

Figure 3: Participation rates in early childhood education for children under 3 in 2004-2005 and 2017-2018 (%, right y-axis) and average inequality (AME) between different educational groups of mothers (left y-axis).

Participation of children under three in early childhood education and care has increased in almost all EU countries since the beginning of the 2000s (Figure 3). The largest increase took place in Luxembourg and Estonia, and the smallest in Sweden and Italy.

In 2018, Denmark, the Netherlands and Luxembourg had the highest participation rates, while Ireland, Hungary and Austria had the lowest. Differences between countries are explained by various factors, including the availability, accessibility and quality of ECEC (Eurydice 2023).

Of the 21 countries studied, Finland’s participation rate was among the European averages both in the early 2000s and in 2017-2018. However, countries with lower participation rates than Finland had already been closing the gap by the end of the period. Compared to the other Nordic countries, Finland’s participation rate was already slightly lower at the beginning of the period, but the gap continued to widen during the period. In Finland, the participation of children under three in early childhood education and care was lower than the European average in all the years covered by the study, while in Denmark, for example, participation rates have long been high.

Children of highly educated mothers more likely to participate in early childhood education and care

Inequalities in children’s participation in early childhood education and care were examined by maternal education, comparing three different educational groups. Looking at differential participation by maternal education over the whole period, France, the Netherlands and Belgium stand out as countries with high levels of inequality, while the Nordic countries have lower levels of inequality (Figure 3).

In Finland, segregation between educational groups is at the European average. The largest difference in participation in early childhood education and care for children under three is between mothers with low and high education – more than 10 percentage points. The differences between the other two comparison pairs are somewhat smaller, with a difference in the probability of using ECEC of around 6 percentage points.

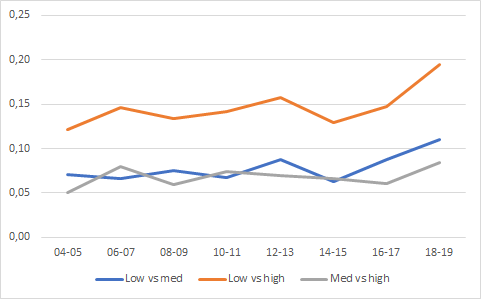

Figure 4: Differences between education groups in early childhood participation of children under 3 years old by mother’s education in Europe, 2004-2019 (% points).

Looking at the evolution of differences between educational groups in all the countries covered by the study (Figure 4), we see that, after a steady trend, inequalities in participation in early childhood education and care have increased. A closer look at the countries shows that inequalities have increased particularly in countries with very low participation rates in the past. In most countries, inequality has remained at the same level over the period, and in a few countries it has even decreased between certain education pairs (see Välimäki et al. 2024 for more details).

In Finland, the differences between educational groups in the participation of children under three in early childhood education and care have remained at the same level throughout the whole study period, both between mothers with low and high education and between mothers with medium and high education. However, the trend in differences between mothers with a low and medium level of education is more difficult to analyse because the group of mothers with a low level of education has become smaller each year.

Participation in early childhood education and care promotes equal opportunities for children

Participation of children under three in early childhood education and care has increased in almost all European countries since the beginning of the 2000s. Participation rates have also increased in Finland, but are still below the European average. At the same time, countries with very low participation rates at the beginning of the period have come much closer to the Finnish level.

While participation rates in early childhood education and care have increased, they have become more differentiated across Europe according to the education of the child’s mother, especially towards the 2020s. However, Finland fares better than many other countries in terms of inequalities, with differences between educational groups remaining around the European average. An analysis of the evolution of inequalities shows that the differences in participation rates in Finland have remained at the same level, especially for education pairs comparing low and medium educated mothers with highly educated mothers. Finland has thus managed to increase the participation rate of children under three in early childhood education and care without increasing inequalities related to the educational background of the mother. On the other hand, inequalities have not been reduced.

In many European countries, inequalities in children’s participation in early childhood education and care are due to problems of availability of services (Pavolini & Van Lancker, 2018). The Council of Europe’s ECEC objectives emphasise not only availability to ECEC services, but also their accessibility, quality and affordability, as well as ensuring the participation of children at risk of poverty or exclusion. However, there are still large disparities between countries (Eurydice 2023).

In Finland, children have a subjective right to early childhood education at the end of parental leave, and the fees are reasonable and publicly supported. For low-income families, the service is even completely free. Indeed, the low participation rate of children under three years of age and the differences between educational groups are largely explained by the home care allowance, a popular benefit for families with young children, rather than by problems of availability or accessibility. Parents with a low level of education – mainly mothers – use the home care allowance for longer than parents with a high level of education (Österbacka & Räsänen 2022; Miettinen & Saarikallio-Torp, 2023). In contrast, participation in early childhood education and care for children over the age of three is very high also in Finland.

In its interim report (Finnish Government 2023), the Finnish Social Security Committee, established in 2020, proposed a reform of the childcare benefit and service system to lower the threshold for parents of young children to return to the labour market. In 2017, an expert group on how to increase participation in early childhood education and care highlighted the need to ensure equal conditions for children’s learning and development, regardless of their social background (Karila et al. 2017). Parents without secondary education have lower employment rates and a higher risk of poverty and social exclusion than parents with higher education, while their children enter early childhood education and care at a later age than other children.

To prevent segregation among children, family policies should be developed in order to promote equal access for all children to quality early childhood education and care services that support their development.

In practice, this means assessing the relationship between early childhood education and care and the homecare allowance as well as the price and quality of early childhood education. Their development must take into account not only the employment and income of parents and gender equality, but also the strengthening of equality among children. For example, the conditions attached to the local supplements of the home care allowance, such as the possible requirement that all children in a family must be cared for at home, may discourage the older siblings from attending early childhood education and care.

Education and employment policies, the quality of working life and opportunities for reconciling work and family life are also important ways of reducing inequalities for both children and parents. For example, supporting the employment of mothers with a migrant background and those with a weak labour market position is an important means to achieve this goal.

Data and methods

The study uses data from the EU-SILC (European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions) population survey from 2004 to 2019, covering 21 countries and a total of 160,999 mothers.

For the inequality calculations, two survey years were combined in order to obtain a sufficiently large number of cases. This also makes the values more stable. Differences between different population groups were obtained by calculating a logistic regression model predicting the participation of a child under 3 in early childhood education by the mother’s education. The results are presented as average marginal effect coefficients, which make it possible to compare the strength of the associations between the different models.

More information

Sanni Välimäki, researcher, THL – Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (sanni.valimaki@thl.fi)

References

Eurydice (2023). Structural indicators for monitoring education and training systems in Europe – 2023: Early childhood education and care. Eurydice report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Karila, K., Kosonen, T. & Järvenkallas, S. (2017). Varhaiskasvatuksen kehittämisen tiekartta vuosille 2017–2030: Suuntaviivat varhaiskasvatukseen osallistumisasteen nostamiseen sekä päiväkotien henkilöstön osaamisen, henkilöstörakenteen ja koulutuksen kehittämiseen. Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriön julkaisuja 2017:30. Helsinki: Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö.

Miettinen, A. & Saarikallio-Torp, M. (2023). Äitien kotihoidon tukijaksot lyhentyneet – väestöryhmittäiset erot yhä suuria. Yhteiskuntapolitiikka 88 (2023):2.

Pavolini, E. & Van Lancker, W. (2018). The Matthew effect in childcare use: A matter of policies or preferences? Journal of European Public Policy, 25(6), 878–893.

Valtioneuvosto (2023). Sosiaaliturvakomitean välimietintö. Valtioneuvoston julkaisuja 2023:26.

Van Huizen, T. & Plantenga, J. (2018). Do children benefit from universal early childhood education and care? A meta-analysis of evidence from natural experiments. Economics of Education Review, 66, 206–222.

Välimäki S., Lammi-Taskula J., Mesiäislehto M. & Närvi J. (2024). Growing inequality and diverging paths in early childhood education and care: Educational disparities in Europe. INVEST working paper 87/2024 & FLUX working paper 16/2024.