Employment of single mothers and fathers has remained lower than that of partnered parents

Policy Brief

3/2023

Juho Härkönen (European University Institute), Marika Jalovaara (University of Turku) and Anneli Miettinen (University of Turku & Kela)

Main findings

- The employment rates of single mothers and fathers are over 10 percentage points lower than those of partnered parents.

- These gaps in employment rates have remained significant since the 1990s, despite an overall improvement in employment rates.

- Educational differences between these groups have also widened. Over 60 percent of single mothers have completed only up to upper secondary education whereas 60 percent of partnered mothers hold tertiary degrees. Differences between single and partnered fathers by education are similar but smaller.

- Differences in educational attainment accounted for approximately one third of the employment gap between single and partnered mothers in the late 2010s. Among fathers, the educational differences explained about a fifth of the employment gap.

- The employment gap is large and has increased among parents with lower or upper secondary education. Among tertiary-level educated parents differences in employment have remained small.

- The employment gaps between single and partnered parents are particularly pronounced among parents of children under 3 years old, but they are also notable among parents of children aged three and older, as well as among parents of school-age children.

A new study (Härkönen et al., 2023) examined the employment rates of single and partnered parents, as well as the factors contributing to the gaps in employment. Among mothers, nearly one-fifth are single parents, while among fathers, the proportion of single parents is about 4 percent.

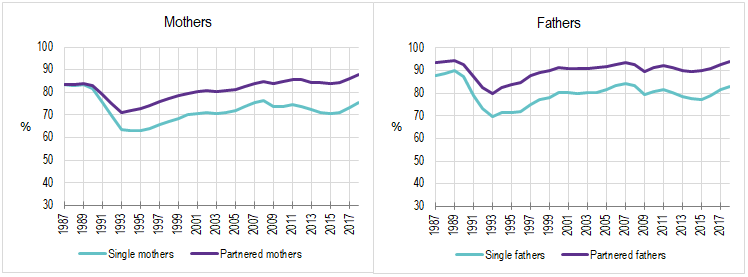

The employment rate of single parents is considerably lower than that of partnered parents (a parent who is living with a partner in cohabitation or marriage) (Figure 1). The employment rates of single mothers and fathers declined more strongly during the early 1990s economic recession than those of partnered parents. Despite the general improvement in employment after the recession and during the 2000s, these employment gaps have not narrowed, and for mothers, the employment gaps have even grown during the 2010s.

In the late 2010s, the employment rate of single mothers was 12 percentage points lower than that of partnered mothers. Similarly, the employment rate of single fathers was over 10 percentage points lower than that of partnered fathers.

Figure 1. Employment rates of single and cohabiting parents (%), 1987–2018. Note: The employment rate has been calculated as the proportion of employed individuals among all parents in the respective group.

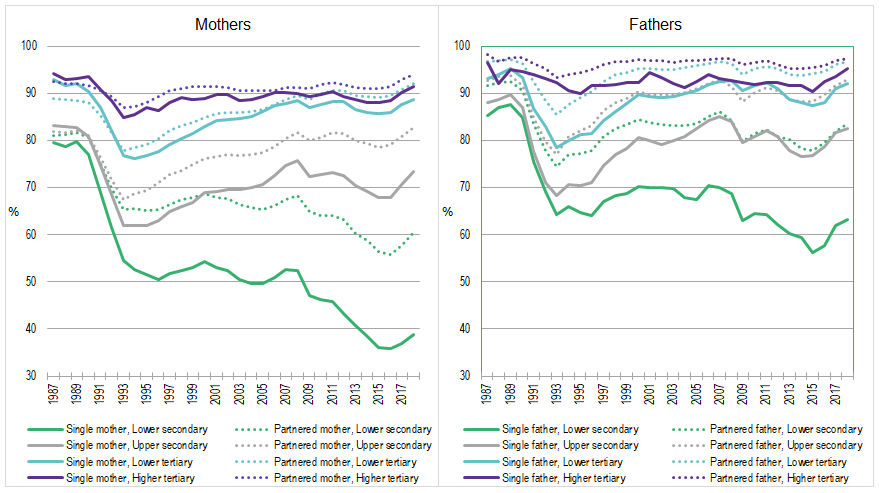

The employment gaps between single and partnered parents are particularly pronounced among parents with no tertiary education (Figure 2).

The employment rate has declined steeply over the past decade for single mothers with only lower secondary (i.e., comprehensive) education. Their employment rate was nearly 20 percentage points lower in 2018 compared to similarly educated partnered mothers. The same difference of 20 percentage points was observed between single and partnered fathers with only lower secondary education.

For parents with upper secondary education, the employment rates of single mothers and fathers are approximately 10 percentage points lower than those of partnered parents. Among parents with tertiary education, the employment gaps between single and partnered parents are much smaller: around 3 percentage points for mothers and about 5 percentage points for fathers.

Despite the fact that overall, employment rates are higher for fathers than for mothers, the employment gaps between family types are quite similar for both genders.

Figure 2. Employment rates of mothers and fathers (%) by family type and education, 1987–2018.

Education explains part of the employment gaps

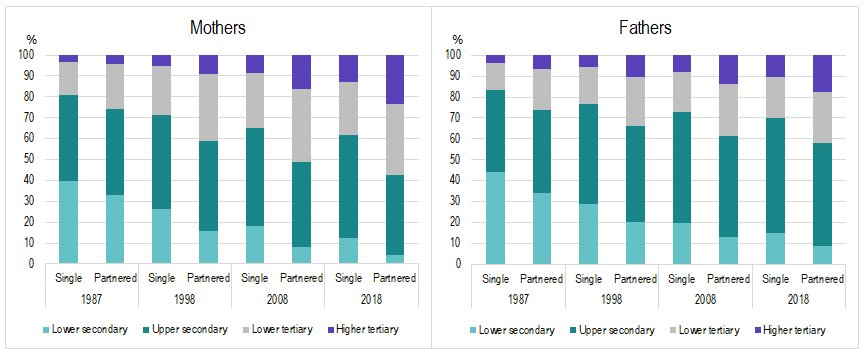

Single parents are, on average, lower educated than partnered parents, and this difference has increased. In the early 1990s, almost 40 percent of single mothers and a third of partnered mothers had only completed lower secondary education (Figure 3). Around one-fifth of single mothers had a tertiary degree, compared to over a quarter of partnered mothers.

By the late 2010s, 13 percent of single mothers had only completed lower secondary education, while this was the case for only 4 percent of partnered mothers. The proportion of mothers with a tertiary degree had increased in both family types, but more strongly among partnered mothers: by the end of the 2010s, less than 40 percent of single mothers and nearly 60 percent of partnered mothers had obtained a tertiary degree.

Similar patterns are observed among fathers: a higher proportion of single fathers have lower educational attainment compared to partnered fathers. By the late 2010s, around 15 percent of single fathers had only completed lower secondary education, compared to 9 percent of partnered fathers. About 30 percent of single fathers had a tertiary degree, while over 40 percent of partnered fathers had obtained a tertiary degree.

Figure 3. Educational distribution (%) of single and partnered mothers and fathers, 1987–2018.

The difference in educational distribution between single mothers and partnered mothers explained about one-fifth of the employment gap between these groups in the early 1990s. In the 2000s, the significance of educational differences in explaining the employment gap has increased, and approximately one-third of the employment gap between single and partnered mothers in the late 2010s can be attributed to the differences in their educational backgrounds.

The pattern is not as distinct for fathers: in the early 1990s, the difference in educational distribution between single and partnered fathers accounted for 14 percent of the employment gap, increasing to 17 percent in the late 2010s.

The proportion of Finnish individuals with only lower secondary education has steadily decreased. Consequently, in the 2010s, a larger portion of the employment gaps between single parents and partnered parents can be explained by differences in employment rates among individuals with upper secondary education as their highest degree. The proportion of individuals educated to the upper secondary level is higher among single than among partnered parents; and, the employment rate in this group is lower than for partnered parents with the same level of education.

Employment gaps largest in families with children under the age of three

The employment gaps between family types were particularly large in families with under 3-year-old children. At the end of the 2010s, the employment rates for single mothers with children aged 1 to 2 was 25 percentage points lower than for partnered mothers with children of the same age. Among children under the age of three, only a small proportion of fathers are single fathers. However, also among single fathers with 0 to 2-year-old children, the employment rate was almost 20 percentage points lower than among partnered fathers with children of the same age.

Notably however, employment gaps were also large for parents with children aged 3 to 6 and with parents of school-aged children. Among mothers with 3 to 6-year-old children, the employment rate was 17 percentage points lower for single than for partnered mothers. Among fathers, the gap was 13 percentage points.

Among parents of school-aged children, the employment rates of unpartnered mothers and fathers was ca. 10 percent lower than those of partnered mothers and fathers.

Conclusions

Since the early 1990s, the employment gap between single and partnered parents – both mothers and fathers – has remained large. The economic downturn that began in 2008 also had a greater negative impact on the employment rate of single parents than on partnered parents. Despite the increases in employment rates in recent years, the employment rate of single parents remains more than 10 percentage points lower.

The strengthening of educational difference between single and partnered parents partly explains these differences in employment. The proportion of individuals with no education beyond the secondary level is higher among single parents, whereas the proportion of those with tertiary education is higher among partnered parents. Additionally, among those with no more than lower or upper secondary education, employment rates are much lower for single parents than for partnered parents. These differences accounted for about a third of the employment gap among single and partnered mothers and about a fifth of the gap between single and partnered fathers.

A significant portion of mothers with children under the age of 3 care for their child at home with home care allowance. The use of home care allowance is somewhat more common among single mothers than among mothers living with a partner (Miettinen & Saarikallio-Torp 2023). Although the use of home care allowance is reflected in the lower employment rate of mothers with young children, the direct effect of parents with children under the age of 3 on employment disparities remained relatively small. This is because the relative size of this group among all parents is quite small. It is also possible that child care services may not adequately meet the needs of single parents: their employment was lower than that of partnered parents also in families with children aged 3 to 6.

The employment barriers for single parents can also reflect employment disincentives: as earned income increases due to employment, benefits decrease, and taxation and day care fees increase; therefore, accepting (additional) work may not necessarily be financially incentivizing. These disincentives can be particularly significant among less-educated single parents, who often receive various social benefits on top of earnings from employment. Further, challenges in reconciling employment and family are greater in jobs that are more common among lower educated individuals, involving evening or shift work, for instance.

Data and methods

The study utilized population register data from Statistics Finland spanning the years 1987 to 2018. An individual was defined as “single”, if they were not married or in a cohabiting union. Individuals in a marriage or cohabiting union were defined as “partnered”, including also registered partnerships. An individual was defined as a “parent” if there were children aged 1to 17 years (for women) or 0 to 17 years (for men) living in the household.

An individual was considered “employed” if they were gainfully employed (as an employee or entrepreneur) during the last week of the calendar year based on data on their main type of economic activity. Parents’ employment rates were calculated by family type, relating the number of employed individuals to the total population within the specific subgroup based on education, age, and the age of the youngest child.

Funding

The research was funded by the Research Council of Finland (decisions 320162, INVEST Flagship and 321264, NEFER-project) and Strategic Research Council (decision 345130, FLUX-consortium).

More information

Anneli Miettinen, University of Turku & Kela, anneli.l.miettinen@utu.fi, +358 50 328 9311

Juho Härkönen, European University Institute, juho.harkonen@eui.eu, +39 055 4685 426

Marika Jalovaara, University of Turku, marika.jalovaara@utu.fi, +358 40 587 98 26

References

Härkönen Juho, Jalovaara Marika, Lappalainen Eevi & Miettinen Anneli (2023). Double disadvantage in a Nordic welfare state: A demographic analysis of the single-parent employment gap in Finland, 1987–2018. European Journal of Population 39:2.

Miettinen Anneli & Saarikallio-Torp Miia (2023). Äitien kotihoidon tukijaksot lyhentyneet – väestöryhmittäiset erot yhä suuria. Yhteiskuntapolitiikka 88(2): 168–175.