Female couples’ likelihood of having a child has increased, but only among those with high education

Policy brief 06/2024

Maria Ponkilainen, Elina Einiö, Marjut Pietiläinen & Mikko Myrskylä

- Childbearing became increasingly common among female couples who registered partnerships between 2002 and 2016.

- Childbearing became more common only among female couples with high education, while it became rarer among couples with low education.

- The importance of higher education became more pronounced over time: among female couples who registered their partnerships between 2002 and 2006, low-educated couples were the most likely to have a child, whereas in later years, highly educated couples were the most likely to do so.

- Educational differences were only marginally explained by couples’ income levels.

- The results suggest that highly educated female couples, almost exclusively, have been able to take advantage of the increased opportunities to have children. Political decision-making should aim to remove barriers to childbearing for female couples with lower levels of education.

The legal recognition of same-sex couples’ family rights in the Finnish legislation in the 2000s has given female couples new opportunities to enter legal unions and have children together. The development of legislation alone does not, however, guarantee concrete opportunities for couples to realize their desires for family life. The practical application of laws and the allocation of resources within the service systems, among other things, also affect the possibility of starting a family.

Family with children in which the parents are of the same sex is not a new family form in Finland. Nevertheless, the need to understand inequalities in these couples’ family formation has intensified alongside increased visibility and new research opportunities following the development of legislation. Our study indicates that differences in childbearing between educational groups have increased because highly educated female couples, almost exclusively, have been able to take advantage of the increased opportunities to have children.

The aims of the study

The number of register-based studies on same-sex couples’ childbearing is still low at the international level, but prior studies from other Nordic countries, such as Sweden, have shown that childbearing has become more common among female couples along with the development of legislation regarding their families (Kolk & Andersson 2020). Educational differences in childbearing have been studied even less. This far the only prior study on the topic found that higher education and higher income were associated with a higher likelihood of having a child among female couples in Sweden (Boye & Evertsson 2021). Corresponding research for Finland has been missing.

The study aimed to examine the likelihood of having at least one child given birth by either woman in female couples who have registered their partnerships, and the changes in that likelihood over time. Female couples in the study had registered their partnerships between 2002 and 2016 in Finland.

Our main aim was to investigate whether female couples’ educational level is associated with childbearing and how the association has evolved in the study period during which legal changes gave same-sex couples the right to, among other things, register their partnerships (2002), access assisted fertility treatments (2007), and share the legal parenthood of a child through second-parent adoption (2009). Furthermore, we assessed whether couples’ income levels explain educational differences in childbearing.

More and more female couples have a child together

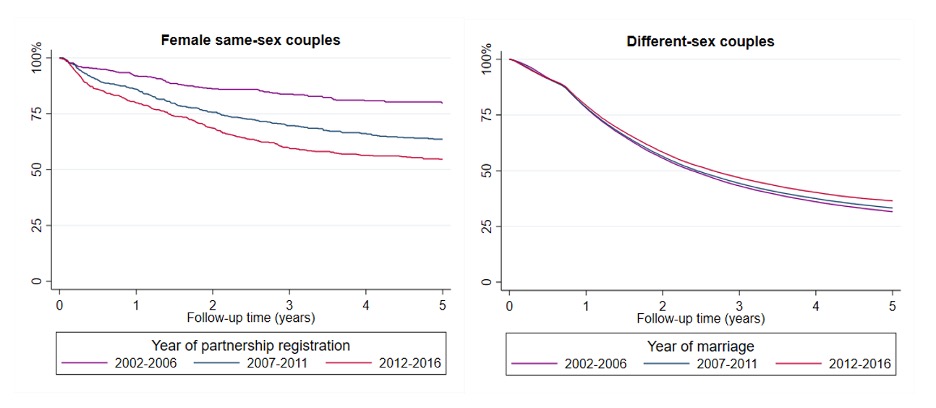

Figure 1 shows female couples’ and different-sex couples’ likelihood of having at least one child within the first five years of their registered partnerships and marriages.

The likelihood of childbearing clearly increased among female couples over time: The likelihood of having a child was 20 percent among couples who registered their partnerships in 2002–2006, 36 percent among couples who registered their partnerships in 2007–2011, and 45 percent among couples who did so in 2012–2016. Female couples’ fertility behavior has thus developed in the opposite direction as compared with different-sex couples, among whom fertility started to decrease within the same period. The increase in female couples’ likelihood of having children is probably explained by legislative reforms which have, among others, improved female couples’ access to assisted fertility treatments.

Figure 1. Female couples’ and different-sex couples’ cumulative probability of not having a child within the first five years of registered partnerships and marriages, by the year of entering a legal union. The lower the curve goes; the more couples have had a child. In the text, we present the probability of having at least one child within five years (1–%).

The likelihood of having a child has increased only among couples with high education

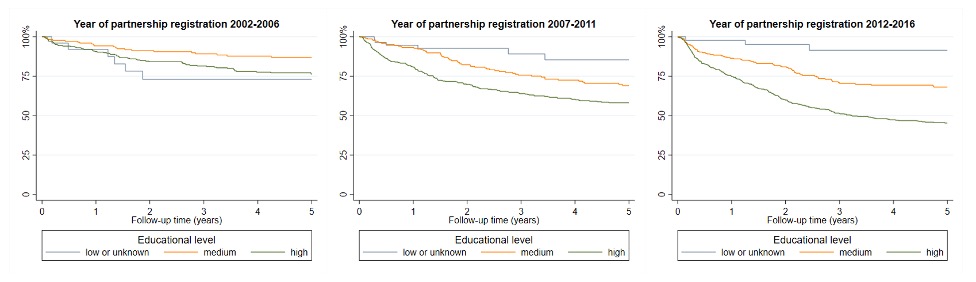

Figure 2 shows that educational differences in childbearing among female couples became more pronounced in the study period. The likelihood of having a child increased clearly only among female couples in which at least one spouse had a tertiary education: The likelihood of having a child was 24 percent among highly educated couples who had registered their partnerships in 2002–2006, whereas the likelihood was already 55 percent among couples who had registered their partnerships in 2012–2016.

Childbearing became more common also among couples in which at least one spouse had an upper-secondary education, but less so than among highly educated couples. Within the same period, the likelihood of having a child decreased from 27 percent to 9 percent among couples in which both spouses had a primary or lower-secondary education or less. Educational differences in childbearing were only marginally explained by couples’ income levels.

The role of higher education became more important over time. The differences between the educational groups changed during the follow-up period of the study: Among female couples who registered their partnership between 2002 and 2006, low-educated couples were the most likely to have a child, whereas among couples who registered their partnerships in later years, highly educated couples were the most likely to have a child.

Figure 2. Female couples’ cumulative probability of not having a child within the first five years of registered partnerships, by the year of entering a legal union and by the highest educational level completed by either spouse. The lower the curve goes; the more couples have had a child. In the text, we present the probability of having at least one child within five years (1–%).

Educational differences in childbearing were clearly larger among female couples than among different-sex couples, which likely reflects female couples’ more complicated paths to parenthood and the importance of resources gained through higher education in their possibilities of fulfilling their desires for parenthood. The observed growing educational differentiation in childbearing among female couples might reflect highly educated couples’ better opportunities to take advantage of the new opportunities to have children.

Several factors may have influenced the association between female couples’ educational level and childbearing, such as changes in legislation and the practices of the social welfare and health care system. Act on Assisted Fertility Treatments, which was enforced in 2007, confirmed female couples’ right to assisted fertility treatments, but the public health care sector refused to offer fertility treatments to female couples until 2019. Female couples were left with the option to seek treatments only in private clinics without a right to receive reimbursement for the expenses from the Social Insurance Institution of Finland (Kela). This has emphasized the importance of socioeconomic resources in having children.

Inequalities in childbearing have widened even if the opportunities have increased

The results of this study indicate that the new opportunities for family formation provided by the development of legislation have not been equally accessible to all female couples. Among female couples with low education, having children is constrained by both their weak position in the labor market and the barriers to family formation faced by same-sex couples.

It is interesting to see how female couples’ access to assisted fertility treatments provided by the public health care sector gradually in university hospitals since 2019 will impact educational differences in female couples’ childbearing in the long run. However, the high demand for treatments involving donated gametes and the long waiting times in the public sector easily result in better-off couples changing over to private clinics to avoid delays and access more treatment cycles. Without the necessary resources, couples have less flexibility in determining when to seek treatments and whether the available options meet their individual needs.

Legal recognition of the family rights of same-sex couples has progressed in a positive direction in Finland, which enables more and more attention to be paid to inequality among same-sex couples. Political decision-making should aim to dismantle the obstacles in family formation through legislation and additionally by means of the allocation of resources and the elimination of all kinds of discrimination, for instance.

Data and methods

The study is based on full population register data on same-sex couples in registered partnerships, provided by Statistics Finland. The study followed childbearing among about 2,000 female couples who registered their partnerships in Finland between 2002 and 2016. According to Finnish legislation, same-sex couples have been allowed to register their partnerships between 1 March 2002 and 28 February 2017 and get married since 1 March 2017.

Childbearing patterns of female couples were compared to about 261,000 different-sex couples who got married within the same period. Event history analysis was used to assess couples’ cumulative probability of having at least one child within the first five years of registered partnerships and marriages.

Furthermore, we examined whether the age or income level of the spouses or the income level of their parents explain the observed educational differences in having children.

More information

Doctoral researcher in demography Maria Ponkilainen, University of Helsinki, maria.ponkilainen(at)helsinki.fi

Ponkilainen, M., Einiö,, E., Pietiläinen, M. & Myrskylä, M. (2024). Educational Differences in Fertility Among Female Same-Sex Couples in Finland. Demography.

Authors

Maria Ponkilainen (1, 2), Elina Einiö (1,3), Marjut Pietiläinen (4,5) & Mikko Myrskylä (1,2,3)

1. Helsinki Institute for Demography and Population Health, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

2. Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock, Germany

3. Max Planck -keskus – University of Helsinki Center for Social Inequalities in Population Health, Rostock, Germany and Helsinki, Finland

4. Statistics Finland, Helsinki, Finland

5. Tampere University, Tampere, Finland

Funding

Ponkilainen was supported by the Alli Paasikivi Foundation, the Emil Aaltonen Foundation, and the Strategic Research Council (SRC), FLUX consortium, decision numbers 345130, 345131, 364374, and 364375.

Einiö was supported by the Research Council of Finland (MISTLIFE 360913).

Myrskylä was supported by the Strategic Research Council (SRC), FLUX consortium, decision numbers 345130, 345131, 364374, and 364375; by the National Institute on Aging (R01AG075208); by grants to the Max Planck – University of Helsinki Center from the Max Planck Society (Decision number 5714240218), Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation, Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Helsinki, and Cities of Helsinki, Vantaa and Espoo; and the European Union (ERC Synergy, BIOSFER, 101071773). Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

References

Aldén, L., Edlund, L., Hammarstedt, M., & Mueller-Smith, M. (2015). Effect of registered partnership on labor earnings and fertility for same-sex couples: Evidence from Swedish register data. Demography, 52, 1243–1268.

Boye, K., & Evertsson, M. (2021). Who gives birth (first) in female same‐sex couples in Sweden? Journal of Marriage and Family, 83, 925–941.

Evertsson, M., Jaspers, E., & Moberg, Y. (2020). Parentalization of same-sex couples: Family formation and leave rights in five Northern European countries. In R. Nieuwenhuis & W. Van

Lacker (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of family policy (pp. 397–428). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hellstrand, J., Nisén, J., & Myrskylä, M. (2020). All-time low period fertility in Finland: Demographic drivers, tempo effects, and cohort implications. Population Studies, 74, 315– 329.

Jalovaara, M., Neyer, G., Andersson, G., Dahlberg, J., Dommermuth, L., Fallesen, P., & Lappegård, T. (2019). Education, gender, and cohort fertility in the Nordic countries. European Journal of Population, 35, 563–586.

Klemetti, R., Gissler, M., Sevón, T., & Hemminki, E. (2007). Resource allocation of in vitro fertilization: A nationwide register-based cohort study. BMC Health Services Research, 7, 210–210.

Kolk, M., & Andersson, G. (2020). Two decades of same-sex marriage in Sweden: A demographic account of developments in marriage, childbearing, and divorce. Demography, 57, 147–169.