Becoming a parent at an older age has different effects for the early careers of women and men

FLUX Policy brief — Knowledge to support better decision making

1/2023

Jessica Nísen, University of Turku

Main findings

- In Western countries, women and men enter parenthood later than in the previous decades.

- This study estimated the impacts of delayed parenthood on women’s and men’s education, employment and income in young adulthood.

- The results indicated that delayed parenthood may add to the educational advantage of women compared to men.

- Delayed parenthood was estimated to diminish the income advantage of men across young adulthood, as delayed entry into motherhood increased women’s incomes.

- This decline in the gender gap in income was largely not explained by changes in education.

- In addition, the study estimated that delayed parenthood improves the incomes and employment of fathers at the time of entering parenthood even more so than for mothers.

Aims of the study

Over the last half century, one of the most profound changes in family formation throughout the Western world has been the postponement of parenthood. Since the 1970s, the average age at first birth for women in OECD countries has increased by one year every decade. This long-term change is embedded in the broader context of a radical shift in the transition to adulthood. This shift is characterized by delays in leaving the parental home, leaving education, and forming marriages; as well the postponement of parenthood.

Young adulthood is a dynamic and demographically dense stage in the life course. This poses a challenge for investigations on the consequences of the timing of parenthood. Parenthood timing is likely to be both influenced by previous education and labour market attachment and may also bear effects on these aspects. It remains unclear to what extent the timing of parenthood affects education and labour market outcomes across young adulthood, and how these effects differ between women and men.

In a new study we investigated how educational and labour market trajectories of women and men in young adulthood depend on the timing of parenthood. The group of researchers came from the University of Turku, the University of Helsinki, the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, the University of Groningen, and the Stockholm University. The researchers used high-quality data from Finnish registers that included women and men born in Finland in 1974 and 1975. Using a novel longitudinal analysis approach, they estimated how a 3-year delay in parenthood would impact educational and labour market trajectories.

Educational and labor market trajectories of women and men differ

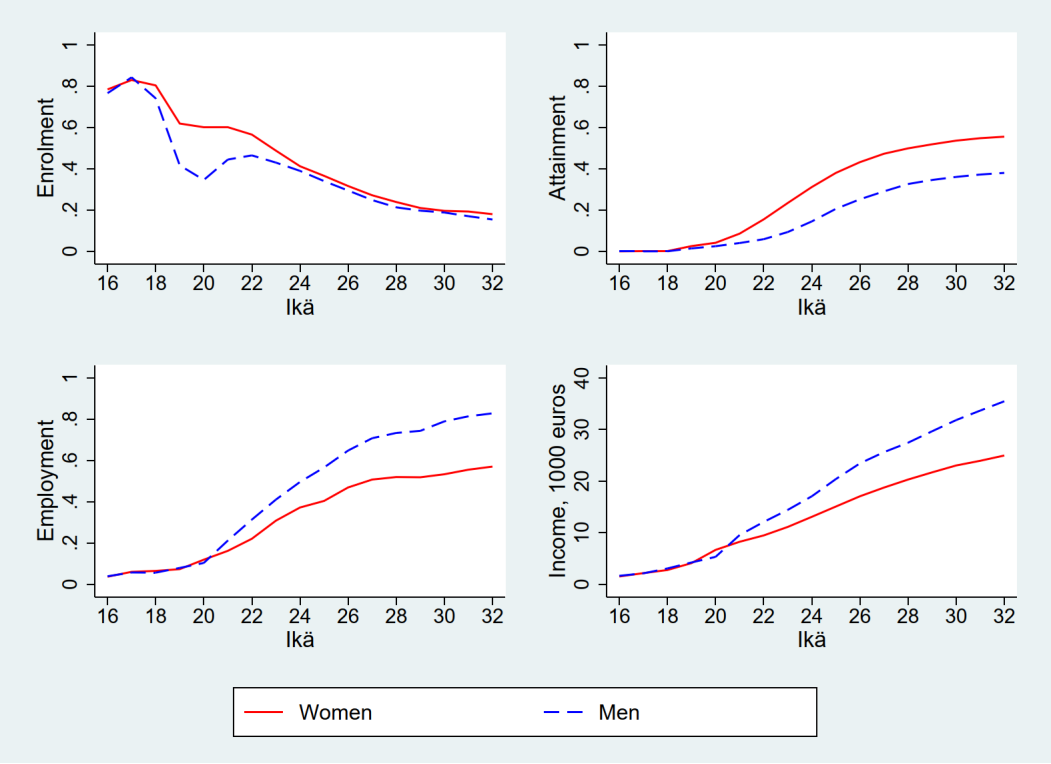

Figure 1. Educational and labor market trajectories among women and men born in 1974 and 1975 in Finland.

Not surprisingly, as Figure 1 illustrates, educational (upper panels) and labor market (lower panels) trajectories of women and men differ strongly across young adult ages in Finland. Women had higher enrollment rates than men in their late teens and early twenties. Overall, women began tertiary education earlier and remained clearly more likely to earn a tertiary degree. In turn, men had higher employment rates and higher earnings than women starting in their early twenties. While the gender gap in employment widened until age 27 and stayed constant thereafter, gender difference in income grew continuously.

Delayed parenthood improved educational attainment of women more

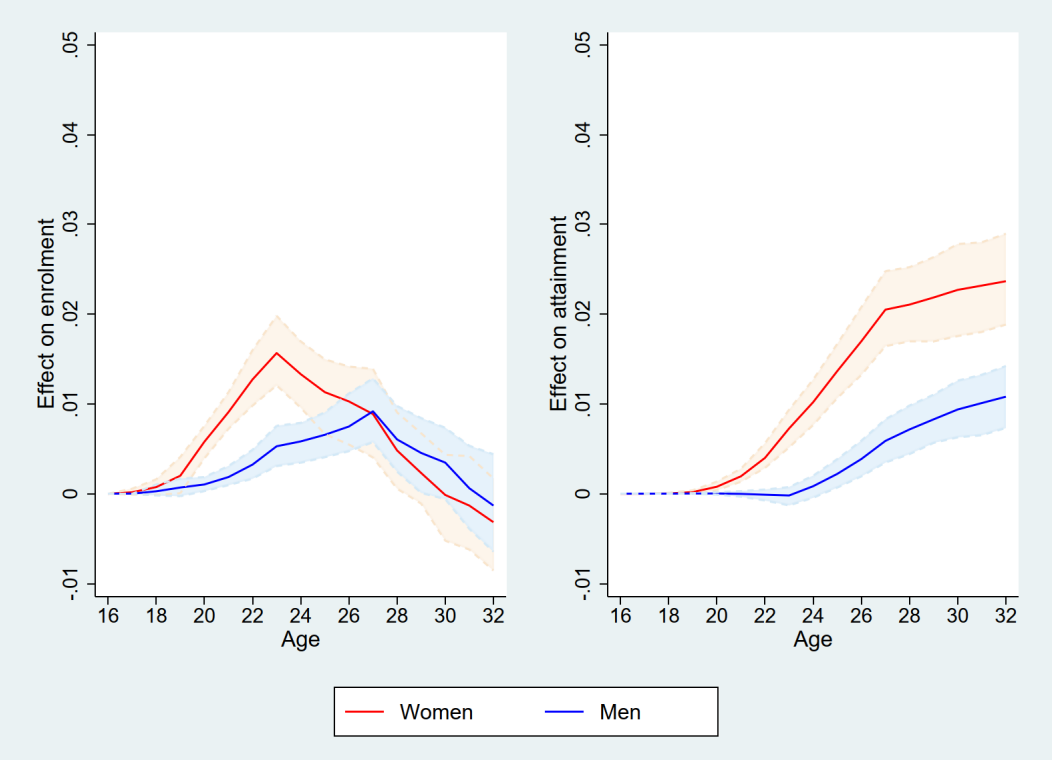

Figure 2. Effects on educational trajectories: the effect of a three-year birth postponement at the population level (population-averaged effect) on enrolment and attainment and 95% confidence interval in women and men.

As shown in Figure 2, the results indicated that in a counterfactual scenario where parenthood was delayed by three years, women gained more in terms of their education than men: a three-year delay was estimated to result in a 2.4 %-point’s increase among women and a 1.1 %-point’s increase among men in the share of those educated to the tertiary level by age 32. These results provide population-level evidence on how delayed parenthood is likely one factor that has contributed to strengthening the educational position of women compared to men over time.

Delayed parenthood strongly improved women’s labour market trajectories

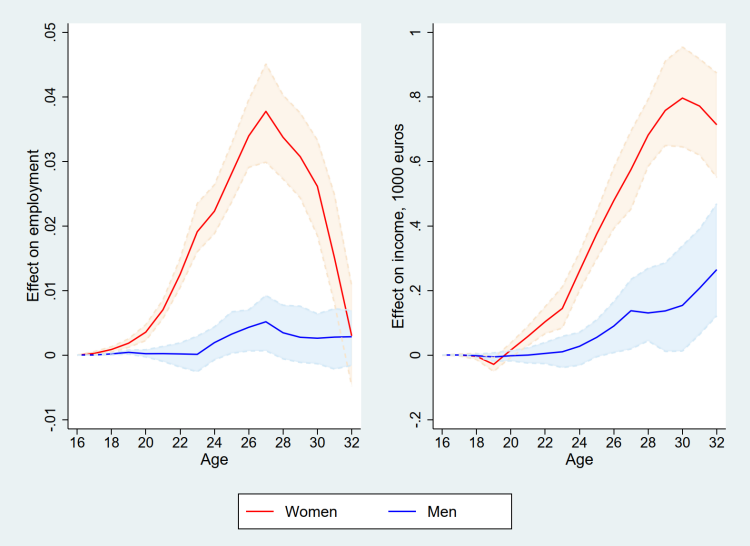

Figure 3. Effects on labor market trajectories: the effect of a three-year birth postponement at the population level (population-averaged effect) on employment and income (and 95% confidence interval) in women and men.

As Figure 3 shows, at the same time, later parenthood was estimated to diminish the income advantage of men across young adulthood. Although incomes of both genders increased in the counterfactual scenario in which parenthood was delayed, the magnitude of the effect was much larger among women. The three-year delay was estimated to have strong but temporary impacts on the employment of women, while employment effects on men were negligible. The employment effect among women reached its peak at age 27, with a 3.8 %-point’s increase in the general population of women. Gender differences in the impacts of delayed parenthood on labour market trajectories were largely not explained by changes in educational trajectories.

At the time of entering parenthood, delayed parenthood improved incomes of fathers more

In addition, the study estimated that delayed parenthood improves the incomes of fathers at the time of entering parenthood even more so than for mothers. The average annual income increased by approximately 6,800 euros among fathers and 4,700 euros among mothers. Also the estimated positive effect on employment was stronger among fathers (12.9%-points) than mothers (9.7 %-points).

While the focus of previous research has been on how the labour market position unfolds after the entry into parenthood, especially among women, this finding adds to our understanding of how parenthood contributes to gendered outcomes in the labour market. This novel finding could help to explain why improvements in gender equality have not been faster.

The time of entering parenthood is a critical time point in the life course, when gender roles in the family are being re-negotiated. Stronger improvements in income at this time point among men may give them a stronger negotiation position over the division of paid and unpaid work in families.

Conclusions

The study focused on Finland, a Nordic country with relatively high levels of gender equality and public support for families, as well as a flexible educational system. This means that gender differences in estimated effects in Finland may be smaller than in many other countries. In Finland, the mean age at entering parenthood has increased since the mid-1970s: it reached 27.6 among women and 30.0 among men in 2000, and respectively 29.7 and 31.6 in 2020.

The results illustrate that delays in parenthood tend to strengthen the educational position of women in comparison to men, while they may attenuate the income advantage of men in early adulthood. These gendered effects which attenuate the existing advantage of men in the labor market raise concerns about the compatibility of motherhood with work life at early stages of the work career typical in young adulthood.

The Finnish family leave scheme enables long absences of mothers from the labor market, and perhaps also the limited part-time work opportunities could create further incentives to postpone return to work among mothers of small children. These notions are consistent with previous findings suggesting that, in the Nordic context, Finnish women who enter motherhood early in life are at a relatively high risk of becoming excluded from the labor market.

Partly, the gendered impacts of delayed parenthood may also result from the fact that women have children on average earlier, which causes stronger interference of parenthood with their early trajectories in education and labor market as compared to men. Further research is needed to quantify the contribution of this fact for the gendered impacts as observed here. A difference of 1.9 years in the average age at entering parenthood in 2020 between women and men suggests that this contribution may also play a role.

Data and methods

The study was based on high-quality data from Finnish registers on women and men born in 1974–75. The study used a still novel method in the field of social sciences, the parametric g-formula. This method allows the exploration of implications of counterfactual scenarios based on observable data. In the current study application, the counterfactual scenario was such that all mothers and fathers had their child three years later than observed in the empirical data. The strength of this method is the estimation of population-level effects, which can be of particular interest also to policy makers. The limitation is that the method relies on causal effects estimated from observable data and needs to assume that all important confounders are measured – an assumption that is often difficult to meet.

Enrolment refers to the share of those in the population of women or men who are enrolled in an educational institution.

Attainment refers to the share of those women or men in the population who possess an educational degree at the tertiary level.

Employment refers to the share of those women or men in the population who are employed at least nine months in the current year. Months on family leave (maternal leave, paternal leave, parental leave, home care allowance) do not count as months employed.

Confidence interval refers to the interval in which an estimate (e.g. an effect) can be expected to lie in the population (e.g. all women and men born in 1974 and 1975 in Finland). A 95% confidence interval refers to the interval in which the estimate would be in the population with a certainty level of 95%.

Funding

The research was supported by the Academy of Finland (nr. 332863, 308247, and INVEST 320162), the Strategic Research Council of the Academy of Finland (FLUX 345130 and 345131; LIFECON 345219, and TITA 293103), the Swedish Research Council, and the European Research Council. Please see the original publication for more details.

Further information

Post-doctoral researcher Jessica Nisén, University of Turku, firstname.lastname@utu.fi

Original publication

Nisén, J., Bijlsma, M. J., Martikainen, P., Wilson, B., & Myrskylä, M. (2022). The gendered impacts of delayed parenthood: A dynamic analysis of young adulthood. Advances in Life Course Research, 53, 100496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2022.100496